None of Deflect's sites have been taken down yet, but they also haven't been targeted by the most sophisticated kinds of attack. The bottom line, as Communications Officer Gerard Harris puts it, is "they need this service and there's no one out there protecting them." There are other non-profit services offering DDoS protection alongside Deflect, but so far none of them has been well-funded or well-publicized enough to keep activist sites consistently safe. It's a rudimentary attack, easy to filter out, but it was enough to bring down the site before they signed on to Deflect's network. One of the sites has been under near-constant attack for the past two years. Their client list is confidential, but it includes independent media and human rights sites in China, Syria, Thailand and Russia.

The method is simple - putting caching servers between the origin site and any visitors - but by offering it for free, the project has become a lifeline to vulnerable sites. "They need this service, and there's no one out there protecting them."ĭeflect is one of the few projects trying to solve the problem, using non-profit funds to run a caching proxy service run out of Montreal. DDoS was born as a protest tool, but it’s grown into a gun for hire, most often aimed at the world’s most vulnerable.

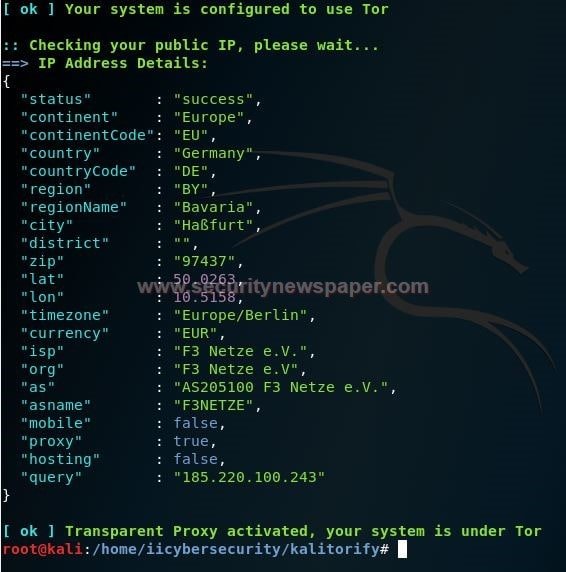

Anonymous ddos tool for free#

But the activist side of DDoS is enabling something much more troubling, a systematic method for silencing dissent that has crippled the internet’s potential for free speech in politically turbulent countries. Inspired by recent Anonymous prosecutions, thousands of people have petitioned the White House to make DDoS actions legal. Some even call it an act of free speech, the digital equivalent of a sit-in. The original model is closer to Anonymous's Operation Payback: a bunch of loosely assembled citizens clogging up a large corporate machine, however briefly. It’s cheap, easy censorship and it’s only getting easier. For a few thousand dollars, you can take down a country's independent media for the length of a news cycle, or shut down a protest website until the scheduled date has come and gone. Attacks are often timed to coincide with an election or protest, or just a peak in nationalist tensions. The past few years has seen similar attacks on opposition party sites and independent media outlets in the Ukraine, Myanmar, Kazakhstan, Belarus, and Morocco, to name just a few. It’s cheap, easy censorship and it’s only getting easier By the time the server recovered, the message was clear: anyone challenging the status quo in Russia was going to have trouble staying online. 4,000 pings per second is a soft touch, as these attacks go, but it was enough to stymie voting for 36 hours. Like any DDoS attack, the goal was a brute force takedown, overwhelming the site with requests until it shut down completely. The website was locked up, buried under 4,000 requests a second, first from a LOIC 1 attack and then from a more sophisticated botnet-based assault. But when zero-hour came, there was nowhere to vote.

It happened in October, when the opposition council held an online vote, building steam towards a long-awaited stable anti-Putin consensus.

The most important denial-of-service attack in 2012 didn't make headlines if you weren't following Russian politics, you probably missed it altogether.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)